How to: Fix a bug inside CoWin

The story of how I managed to fix a bug inside India’s national vaccination delivery platform

November 24, 2021

If you're an Indian reading a blog on the internet written in English, you probably know what CoWin is. If not, here's a one line summary: it's an online vaccination delivery platform, built and sustained under the aegis of India's National Health Authority.

In April of 2021, people over the ages of 45 became eligible for vaccination in India. Both of my parents received their first doses on the first of April, and it felt safe to finally let ourselves collectively breathe a sigh of relief.

That things turned out very differently is well-known; and there's enough content out there if you're interested in reading and exploring more about what happened. The capital city was ravaged by the second wave, and our household was swept along with it. The 4th of May brought the first glimmer of hope in multiple weeks in the form of a vaccination appointment for my sister and I.

Hope – and vaccination appointments – had been hard to find in the preceding three weeks. During the first wave we had the privilege of looking at graphs and numbers with a sense of detachment; in April, everyone I knew became pixels on a curve that rapidly dwarfed last year's peak, with no bend in sight.

The appointment, therefore, represented the possibility of a fleeting return to "normal". India had decided to extend its vaccination program to those in the 18-45 age-group only days earlier. The administration and management of this drive was being done through CoWin.

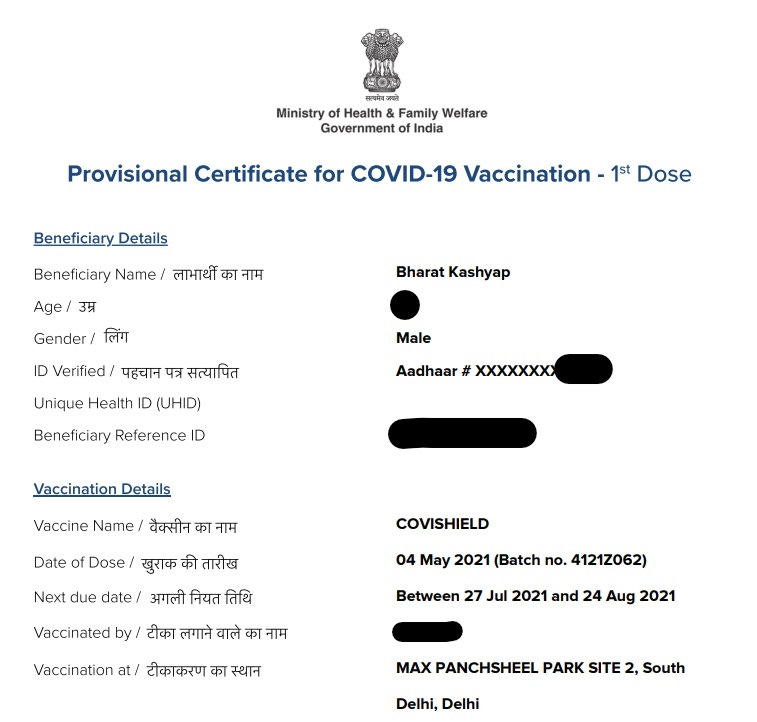

With some persistence, and a bit of luck, I managed to writhe through crowds, albeit virtual, and book a slot. The first shot was had, and I generated my certificate of partial vaccination through a two-step process on the portal. All relatively smooth, except one issue: my age was printed incorrectly.

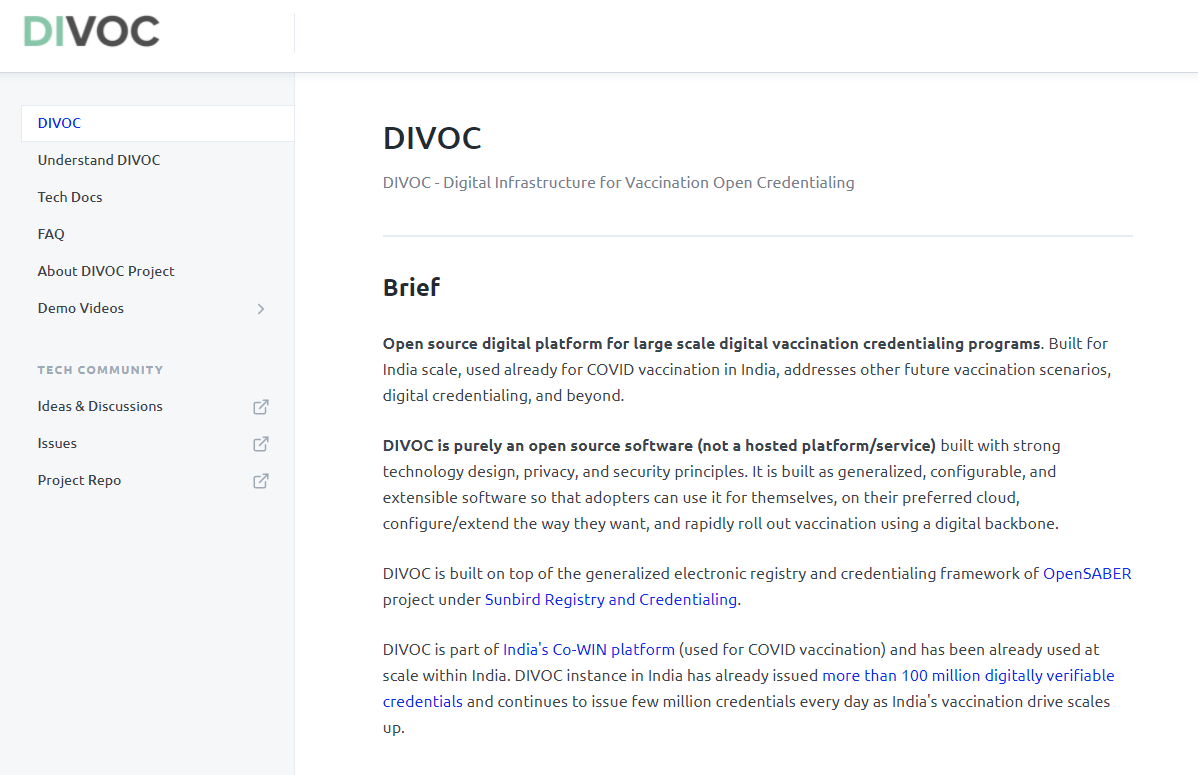

It didn't bother me too much at the time – there were more pressing issues at hand – but a few weeks later, some casual exploration on a Sunday brought me to "DIVOC"

It turned out that CoWin is based, in large part, on an open-source project called DIVOC – short for "Digital Infrastructure for Vaccination and Open Credentialing"– built and maintained by the eGovernments foundation, offered under the MIT license.

What that essentially means is that it is free to use for anyone: be it small, private entities or massive ones like the Government of India. What that also means is that its code is freely available for anyone – including you and me – to access.

The adoption of "open-source" technology for and by the Indian government has not happened overnight. The beginnings were made when Aadhaar, a national unique identity project, demonstrated that it was possible to handle "India scale" without proprietary products to hold it up.

The transition has not been easy, and it is far from even being considered close to complete: selling software to government has long been the arena of international technology giants and consulting firms that remain difficult to dislodge, as the MIT Technology Review explains:

No one gets fired for hiring Deloitte or IBM. And when vendors keep getting the same kind of work they've done badly, there's no incentive for them not to build a shitty system. Government requests for proposals are often written so they only fit one or a few vendors. You might see a yes or no box for, "Vendor must have worked on a healthcare system that serves over 500,000 people." I don't care whether that system exists, I want to know whether people who have to use it hate it.

A recent, relevant example is "VAMS" – The Vaccine Administration Management System – built for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the US by Deloitte, as part of a $44 million no-bid contract. What the software does is trivial at best – it does not include certificate generation – and has been met largely with indifference or criticism, as the MIT Technology Review, again, describes:

Instead, "VAMS has become a cuss word," Marshall Taylor, head of South Carolina's health department, told state lawmakers in January. He went on to describe how the system has badly hurt their immunization efforts so far. Faced with a string of problems and bugs, several states, including South Carolina, are choosing to hack together their own solutions, or pay for private systems instead.

Open-source GovTech

Invariably, governments are reliant upon legacy software: technology that was purchased and installed decades ago, with costly annual maintenance contracts. To disrupt this is to attempt a notoriously difficult task of software archaeology, but there is a clear framework to evaluate its benefits:

- Ownership: The primary, and very significant, shift that open-source brings inside government technology departments is one of ownership: instead of vendors on whom all responsibility for failure can be pinned, they must step up and own their own software in letter and spirit. It necessitates the cultivation of expertise inside the government instead of it remaining perennially in the custody of those outside – people with no incentive to ever transfer it.

- Extensibility: Ownership breeds extensibility. Open-source software owned by the government can be suitably modified, extended and re-configured to adapt to additional use-cases without tedious contract renegotiations, or worse, additional tendering.

- Community:

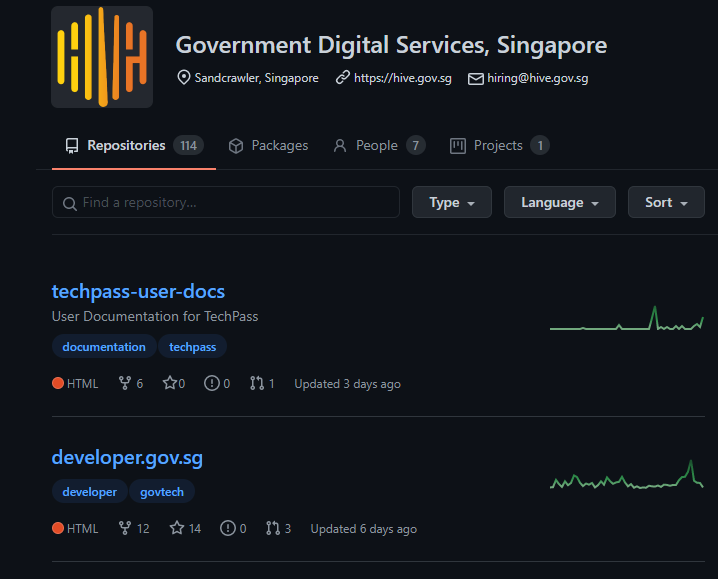

As XKCD wryly depicts here, almost all of modern digital infrastructure is supported by open-source software, maintained by communities of contributors. It is perhaps the most under-appreciated success of the internet: how thousands of people collaborate remotely to craft software with no monetary reward. For government technology, leveraging this aspect of open-source culture remains the most elusive. Countries like Singapore have taken strong strides to engage this community with their "GovTech" setup.

A beginning was made in India by the National eGovernance Division which launched its own version of GitHub called "OpenForge", but it remains far from being the vibrant repository of government software that it was envisaged to be.

To engage the open-source community is to be able to build features fast, and more importantly, fix issues faster. Issues like the incorrect age being printed on millions of vaccination certificates.

Not just a number

Over at DIVOC, the issue board had on it a bug report titled "Age is reflecting incorrect". As you'd expect, it rang a bell. A discussion was already underway; a few hours of looking into the code and some help from friends later, I was able to identify a solution. It was simply the matter of taking one's birth month into account, which the existing code had missed. A single-line fix.

I proposed it to the maintainers of the project, not entirely sure if a response would be received.

Within two days, additional members of the community chimed in to suggest alternative implementations, different potential sources of error. It was pointed out that this fix would work only for a certain proportion of users; nevertheless, it would be an improvement. A final fix was agreed upon, and my submission — the single line fix — was merged into the main codebase. The next day, it was released.

Software written for population scale in India, will, hopefully follow this lead: the best traditions of free and open-source software (FOSS) being leveraged to craft codebases – and institutions – robust enough to withstand scrutiny and gracious enough to accept contributions that can improve efficiency, and solve issues of any scale.

If you're interested in contributing fixes, here is the issue board. Find something and try fixing it!